I'm Alex Berman and you're watching SELLING BREAKDOWNS.

Whenever you buy a complex piece of equipment such as a TV or a car, do you ever wonder;

how exactly it all came together?

Well, ever since the industrial revolution, that "how" has been a vital question for

many businesses.

Today, we're going to look at how in post-war Japan, Toyota helped to create one of the

smartest production systems that we have, named "Just In Time".

We'll look at how it works and how you can apply the philosophy and practises to many

other areas of business.

After World War 2, Japan faced some difficult problems; they didn't have a lot of cash,

resources were scarce, and there wasn't a lot of free land to expand factories.

However, Taiichi Ohno at Toyota managed to turn these problems into advantages by slowly

creating the Just In Time system.

The idea didn't all come at once, it's more that through the 50s and 60s, various

changes were implemented and improved until the 70s were the wider world began to realise

the benefits and adopted a similar approach.

So, what is Just In Time?

The philosophy is to make the entire production system only work with what it needs and to

minimise wait times between each stage.

The big saving is normally around inventory.

Before Just In Time, a company would keep a warehouse filled with the parts and raw

materials it needed.

When supplies were getting low, they would reorder when they had just enough to keep

going until the new delivery came.

But Toyota realised; what if you just keep making that same order, as soon as the next

one arrives?

That way, you never need to keep this stockpile of spare parts.

The cost savings were huge since warehousing is seriously expensive; you need to pay for

a massive space, power, staff, security, and for parts that are just sitting there, waiting,

not making you money or adding value to your product.

And this is the core of Just In Time; you look at each area of production and ask "is

this adding value to the product?"

If it isn't, maybe there's a better way to do it.

You cut everything down to it's most efficient form, with almost no room for error, which

is where the risk in Just In Time lies.

Toyota used Japan's relatively small size to its advantage.

You could rely on suppliers delivering exactly on time because they only had to travel small

distances.

If you get problems with supply then it can shut down the whole system.

But it's normally worth the risk; the savings are huge, on inventory and staff costs.

More than this though, you are forced to create a working philosophy that there is no room

for error; you don't have spare parts or spare time so you have to make sure everything

functions perfectly.

Often efficiency comes at the cost of quality, but not in this case.

In Just In Time; you are forced into quality in order to be efficient.

That's why it's applicable to many other areas of business.

The best way to think about it is if we simplify everything to two approaches; Just In Time

and Just In Case.

With Just In Case, you are trying to minimise risk by always giving yourself a buffer.

You'll carry extra stock so you can swap out faulty items.

You'll over-staff certain areas because they've occasionally had too much work to

deal with.

You'll support a service that just a few customers ask for.

With Just In Time, you don't simply cut these areas and cross your fingers that nothing

bad happens.

No, you work out how you can avoid them happening in the first place.

Because this is money that is wasted unless a bad thing happens, you're effectively

investing in mistakes.

Better quality control means staff can trust the stock they have so they don't need a

back up.

As for workloads, the only reason one department is hit by a workload they can't handle is

because there is not enough visibility between departments.

If your sales team know the capacity of production and its current status, then they won't

put in an order that can't be filled.

And as for offering a service with limited customer appeal, well, maybe you cut it out

completely or just find a way to merge it with other services so the resources it requires

are absolutely minimal.

When done well, the Just In Time philosophy should be good for moral too because the whole

point of it is telling your staff "I'm trusting you to perform consistently" and

I think most of us respond well to that kind of respect.

Wanna learn more about business theory and history?

Be sure to like and subscribe to be notified of our next segment.

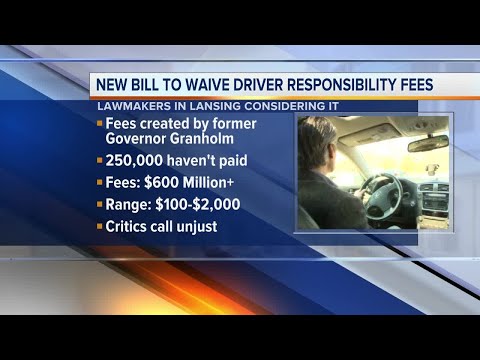

For more infomation >> New bill would waive Michigan driver responsibility fees - Duration: 1:29.

For more infomation >> New bill would waive Michigan driver responsibility fees - Duration: 1:29.

For more infomation >> I challenge you: Die Surf-Challenge (Deutsche Gebärdensprache) - Duration: 9:36.

For more infomation >> I challenge you: Die Surf-Challenge (Deutsche Gebärdensprache) - Duration: 9:36.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét